Summary: I built a spreadsheet model that forecasts the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths depending on a number of factors including the effectiveness of controls and herd immunity. You can copy the model, edit the assumptions, and run your own scenarios.

How will all this end?

That’s the question many of us are asking.

After a month or more of sickness, sheltering in place, social distancing, working from home, not being able to work at all, homeschooling children, loneliness, or all of the above, we’re all eager for things to get back to normal.

We want to know when our society can begin to reopen, what will happen when it does, and what precautions we’ll have to continue to take and for how long in order to stay safe. Most of all, we want to know when we’ll finally get rid of the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

The months of March and April, in which we worked to “flatten the curve,” were just the beginning. The coming of May marks the beginning of the end — a very hopeful but also risky, longer, and potentially much more deadly stage of this pandemic.

So what does the future hold? Given how little we still know about the coronavirus, it’s impossible to predict the future with much accuracy. However, modeling can give us a better idea of the shape of things to come, and suggest a range of likely outcomes.

To that end, I’ve updated my Simple Coronavirus / COVID-19 Model in Google Sheets to include new information we’ve learned in April.

This post is part of a series on modeling the COVID-19 impact using spreadsheets. Be sure to read the other articles in the series for the latest models and information.

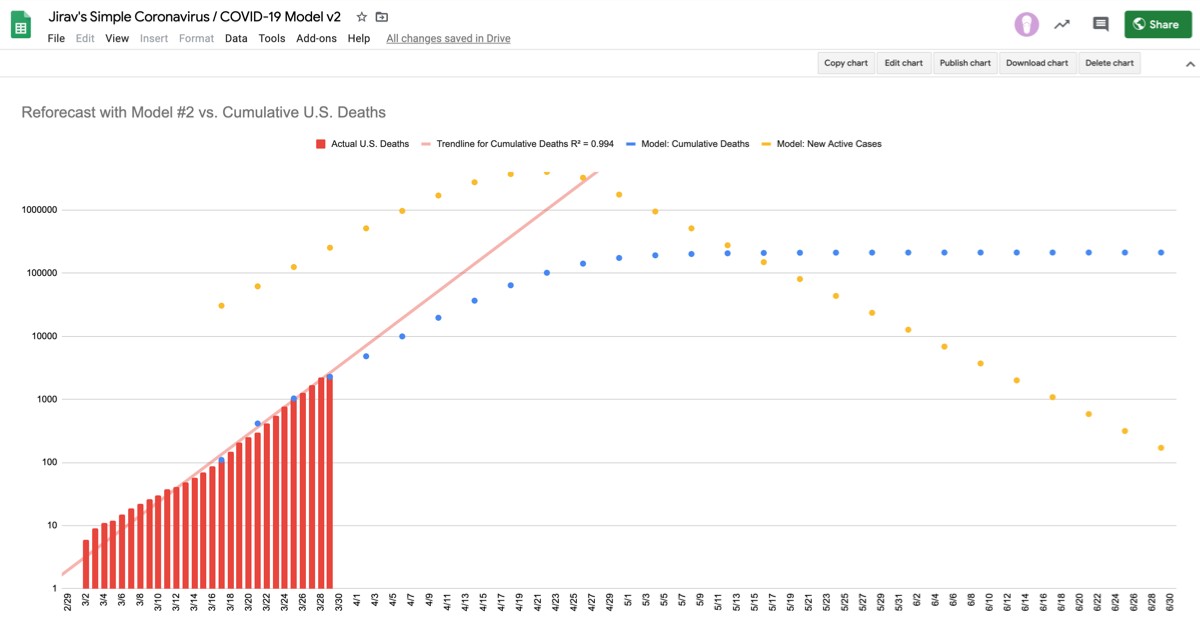

- Part 1: A simple model for forecasting the impact of coronavirus and controls (March 9)

- Part 2: Reforecasting the U.S. COVID-19 Impact (March 30)

- Part 3: Forecasting the End of COVID-19: Herd Immunity (April 29)

What we learned in April

COVID-19 might not be as deadly

We know there are many people who have had COVID-19, never got tested, and recovered. What we don’t know is how many of those people are out there. That’s in part due to an ongoing lack of testing capabilities, and also because many people who get COVID-19 apparently do not have symptoms, or have very minor symptoms, so have no reason to seek out the tests that are available.

This situation has caused a lot of confusion about the risks associated with getting the disease. Probably the most well-known number is the WHO’s initial 3.4% estimate on March 3. But that number was the crude mortality rate, which is high because many infections are going undetected.

What we want to know is the infection fatality rate, which represents the true odds a patient will die. To calculate this ratio, we need to know how many people total have been infected, not just confirmed cases. In my previous version of this model, I used a factor of 6 for undiagnosed cases based on a range of 5 to 10 as suggested by a study published in Science. That would indicate a mortality rate of around 1%.

Based on new studies, it now appears that the virus may be much more common than we thought in the United States, and therefore much less deadly, too — but still probably much more deadly than the seasonal flu.

Here is a sampling of those studies. Note that many of these studies have not yet been peer reviewed, so we have to take the results with a grain of salt:

- Italian town of Vò - March 6 - approx. 0.06% mortality rate

- NBA players - March 11-19 - indicates infection rate at 72 times the number of reported cases

- Hubei, mainland China - March 30 - mortality rate of 0.39 to 1.33%

- Los Angeles County & USC - April 20 - mortality rate of 0.1 to 0.2% (28 to 55 times the number of reported cases)

- Santa Clara County - April 14 - mortality rate of .12 to .20% (50 to 85 times the number of reported cases)

- New York City - April 27 - mortality rate of 0.5 to 0.8%

I’m particularly interested in the Los Angeles and Santa Clara studies because they are recent (April 17 and 20) and indicate a mortality rate 5 to 10 times lower than the previous model, and much closer to the fatality rate of the seasonal flu, which is around 0.1%.

Another interesting data point comes from the government of Iceland, which has made a goal of testing everyone in the country. As of April 28, Iceland has a case fatality rate of 0.56%.

While there is plenty of variation in these studies, it’s hard to imagine that they’re all flawed.

Lockdowns are harming our economy

Shutting down stores, offices, and schools may be stopping the spread of the virus, but it is also sending shockwaves through our economy not seen since the Great Depression. A White House economist warned Tuesday that the jobless rate could hit 16% to 20% by June.

Sergio Rebelo, an economist at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, estimates the cost of a yearlong lockdown to be around $4.2 trillion, or 22% of the economy.

Add to that the cost of stimulus spending by the federal government, which is already up to $3 trillion, with no end in sight.

Lastly, there is the difficult-to-quantify aspect of a shutdown on society. We all are experiencing that. How long can we keep on going, even if we wanted to?

We aren’t going to have large scale testing

One thing that would really help our reopening strategy is large scale testing and tracing. We should be testing as many people as we can as frequently as we can. If someone tests positive, we should track down everyone they have had recent contact with and test them, too. Then we quarantine all the individuals who have tested positive until they are no longer infectious.

This would dramatically reduce the transmission rate of the virus without us having to resort to draconian lockdowns or other more restrictive social distancing measures. Unfortunately, we do not have this capability now, and it is unlikely that we will have it anytime soon. Therefore, I’ve left this factor out of my model.

A vaccine is still a (relatively) long way away

While we’re all hoping for a vaccine, the odds of us getting one anytime soon are slim. Dr. Fauci, the leader of the White House coronavirus task force, says a vaccine is 12 to 18 months away. And this is likely an optimistic timeline, given that the typical vaccine takes 10 years to develop.

What we still don’t know

We don’t know whether or not those who get COVID-19 develop immunity in the future. Based on our experience with other viruses, this is likely, but not a sure thing. For the sake of being able to build a model that incorporates herd immunity, we’ll assume that people who get infected and recover acquire full immunity.

The two options

We have two options and the first option — an indefinite lockdown until we develop and deploy a vaccine — isn’t really an option at this point. Individual states are already beginning to open up. Therefore, whether we like it or not, the country has started down a path to “herd immunity.”

Herd immunity is when enough individuals in a population have gained immunity that the virus begins to die off on its own. In other words, the virus can’t grow because it lacks enough new hosts. Coronavirus has a reproductive rate of 2.5, meaning that about 60% of the population needs to get infected to achieve herd immunity.

Thus, our goal in this scenario is to reach herd immunity without causing cases or deaths to peak to the point where it overwhelms the health care system.

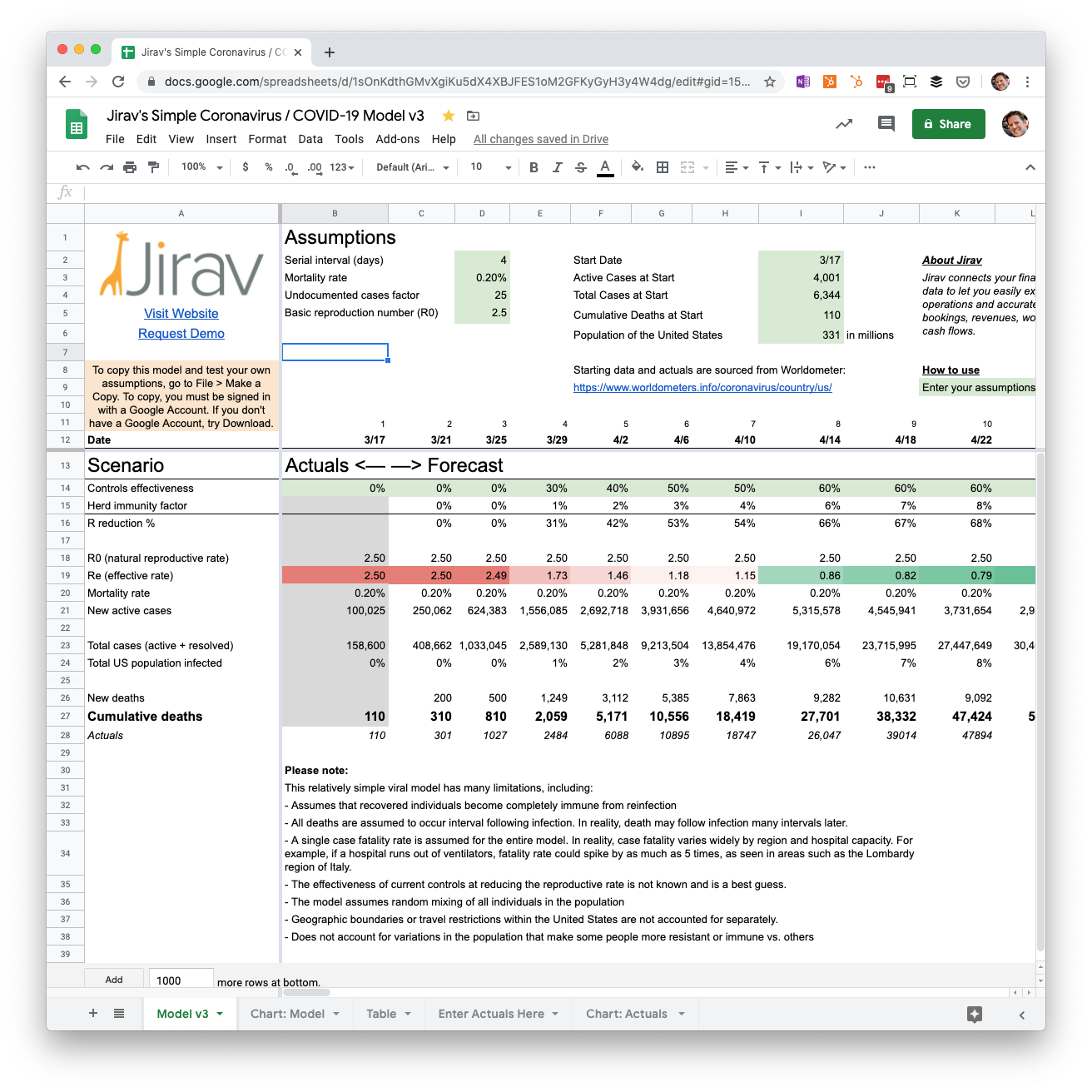

Modeling the scenarios

Here are the starting assumptions used in version 3 of the model:

Starting assumptions

- The serial interval is 4

- The mortality rate is 0.2%

- There are 25 undocumented cases for every confirmed case of COVID-19

- The basic reproductive number is 2.5

- The population is homogenous and mixes randomly

- A single fatality rate is assumed for the entire model

- Deaths are assumed to occur the interval following infection

- Recovered individuals become 100% immune

- No vaccine is developed

- A “test and trace” program does not materially impact the reproductive rate

- Controls are gradually relaxed in a linear fashion between the beginning of May and the end of December

Heads up: These assumptions in the Google Sheet may change as I reforecast the model.

Visualizing the scenarios

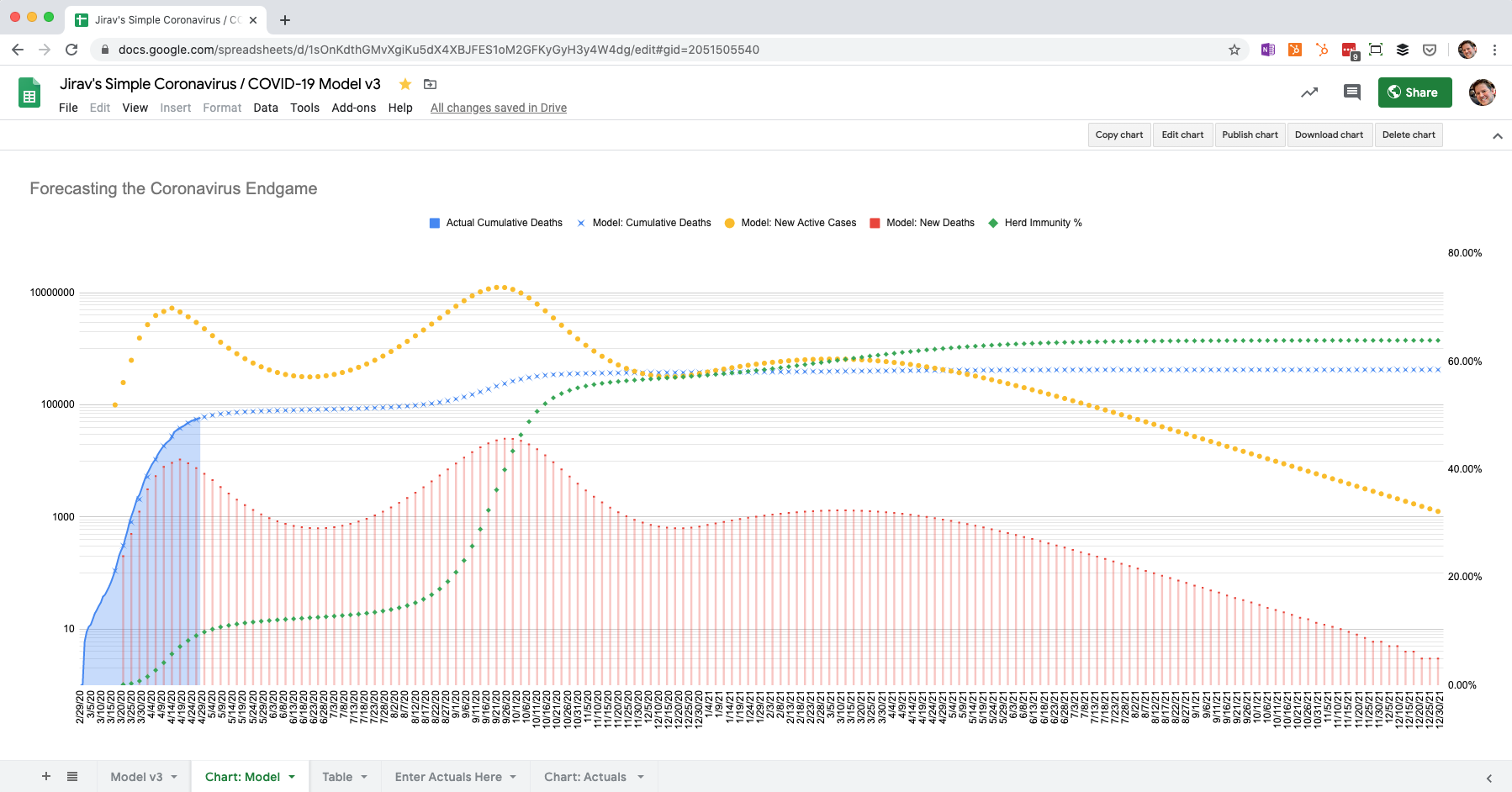

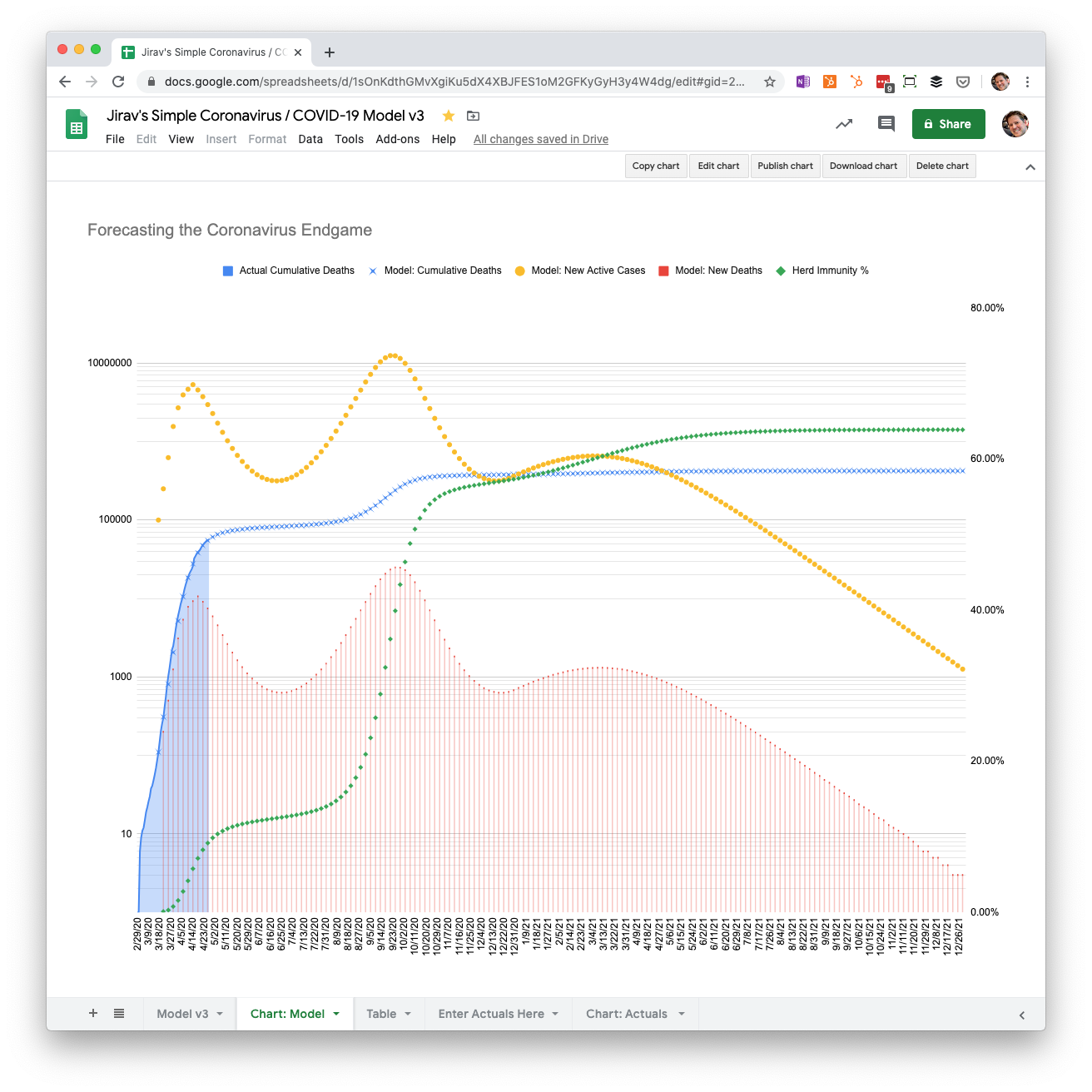

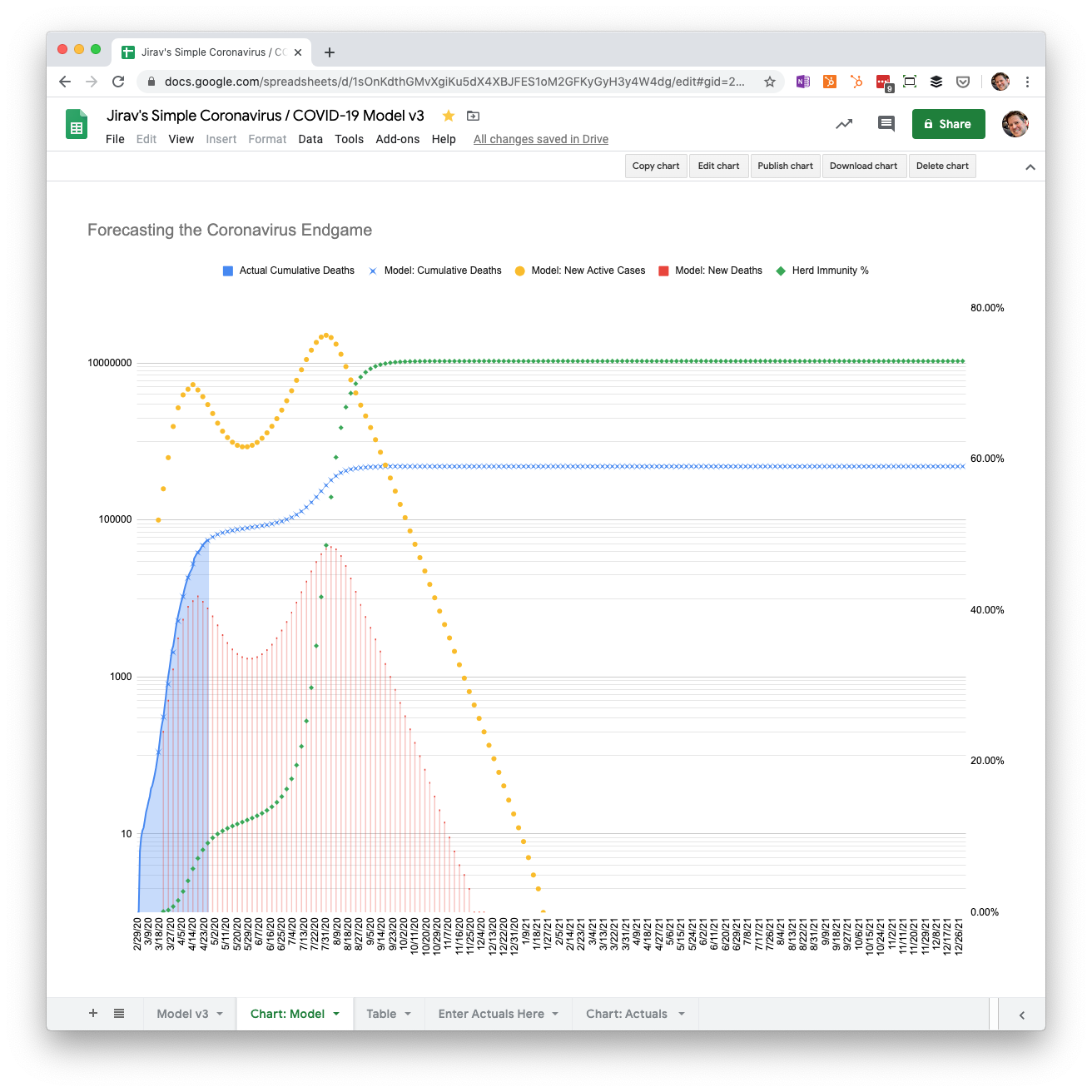

Here’s a chart showing the projected new active cases, new deaths, cumulative deaths, and herd immunity % based on drawing down social distancing controls linearly from May through December.

Important: The left-hand vertical axis in these charts is on a logarithmic scale. This means that small differences in peaks and valleys are much larger than they appear. For instance, there is a peak in the chart below in late September. That peak is visually not all that different from the peak in April, but is more than twice as large.

Gradual reopening from May through December with 0.2% mortality

Let’s start with the mortality rate suggested by the Los Angeles and Santa Clara County studies in April. This is five times less than the previous model.

Notice that the current lockdown caused a significant reduction in deaths. But then they shoot back up, peaking in late September. Herd immunity also jumps up to over 50% in October. From that point, deaths gradually decline each period until they are close to zero at the end of 2021 (not 2020). By December of 2021, 423,000 people have died and 64% of the population has been infected. Herd immunity has been achieved.

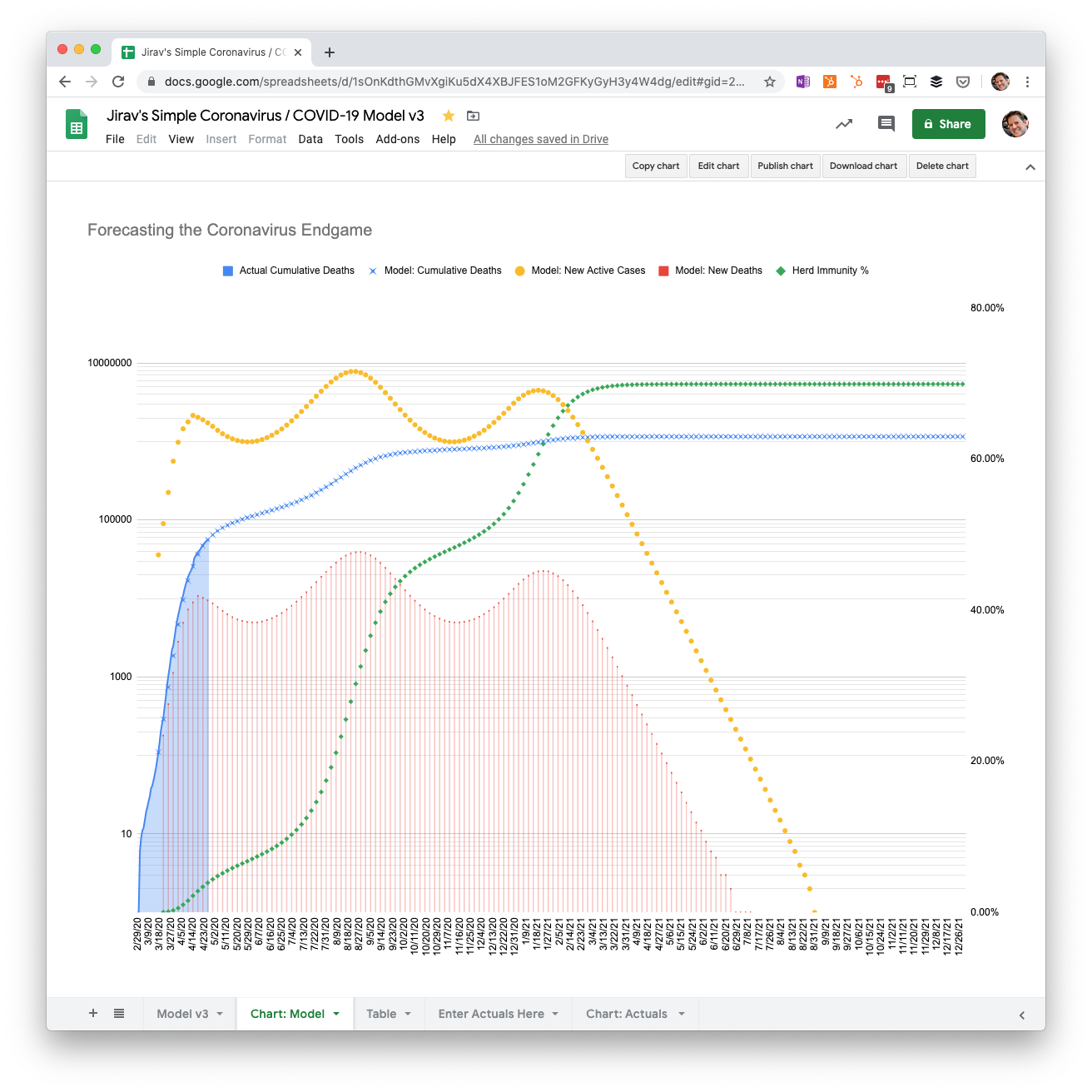

Gradual reopening May through December with 0.5% mortality

What if the true fatality rate is not as low as we hope? Perhaps it is closer to the case fatality rate in Iceland, where the government is trying to test everyone.

At 0.5% mortality, five times that of the seasonal flu, we end up with about 1.16 million deaths. However, we reach the end point sooner in June of 2021, with peaks in deaths in August 2020 and January 2021. The peak in August is about 4x what we just experienced in April, and in January is about twice as bad.

We could run the scenario for higher mortality rates, but there’s not much of a point, given the high number of deaths that will occur in a herd immunity scenario. It’s difficult to imagine politicians and the public being OK with more than 1 million deaths. However, if you want to run that scenario, you’re welcome to copy the Google Sheet and give it a try.

Gradual reopening May through December with 0.1% mortality

What if, on the other hand, the mortality rate is the same as the seasonal flu? In this scenario, we end up with 240,000 deaths, a peak in November more than twice as large as April, and an end point in February 2021.

This is why it’s not so simple to just say, “COVID-19 has the same death rate as the flu, so we should just live with it.” The difference between coronavirus and the flu is that we have herd immunity for the flu, so cases are spread out over a longer period of time, and don’t overwhelm our health care system capacity.

Even if COVID-19 ends up being similar to the flu in terms of deaths, which still seems unlikely, it is necessary to gradually reduce controls to avoid another spike in hospitalizations like the one we saw in New York City.

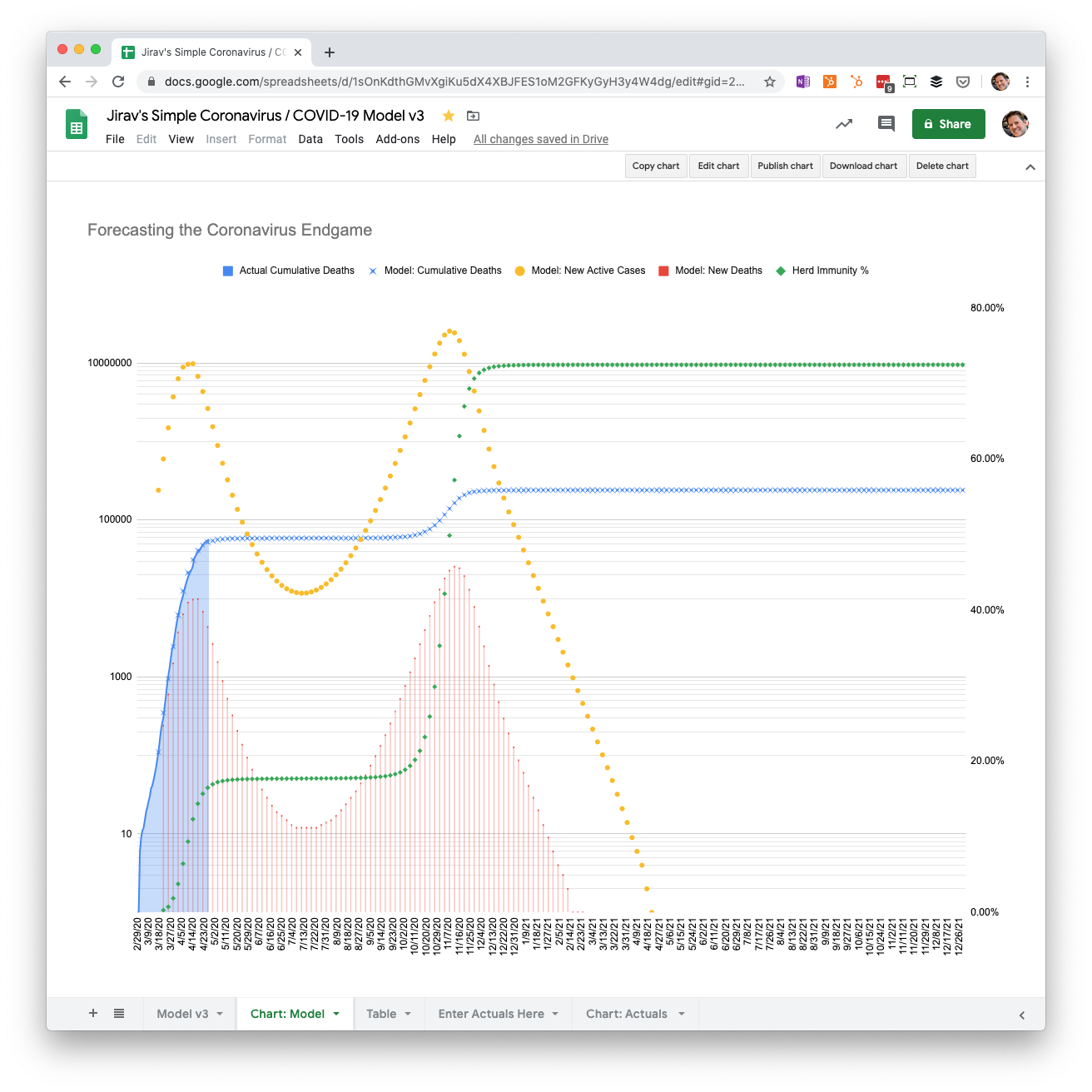

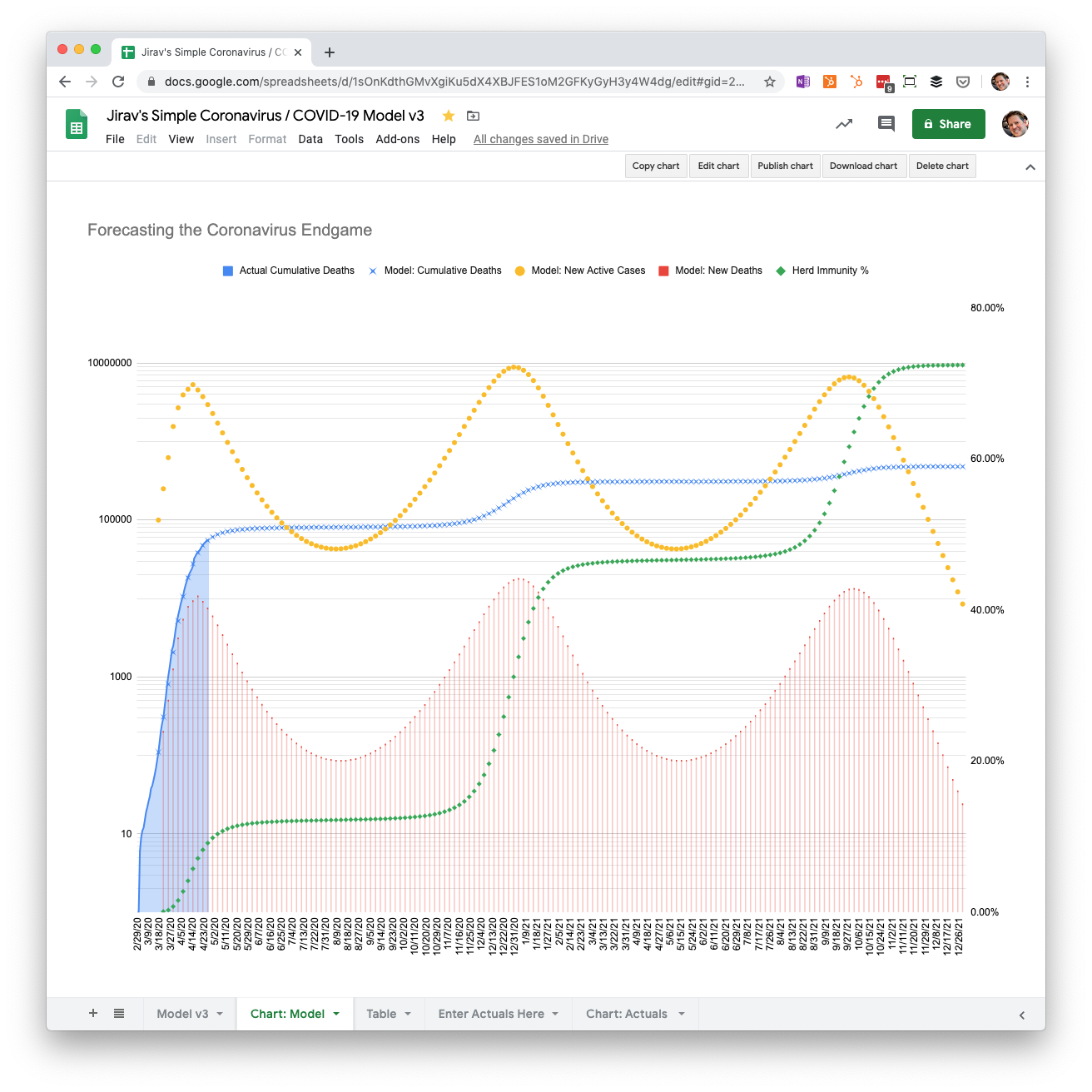

Faster reopening May through August with 0.2% mortality

What happens if we go back to our original scenario and only change how quickly we relax social distancing controls?

If we double the speed that we reopen, there’s a peak of deaths in early August more than four times as large as the one in April. However, the virus has run its course by December of this year.

The ultimate cost, assuming the healthcare system isn’t overwhelmed, is an additional 60,000 lives, for a cumulative death count of 483,000.

Much slower reopening May through August 2021 with 0.2% mortality

For our last scenario, what if we spread out the reopening gradually from May through August of next year?

Cumulative deaths end up in a similar place at about 480,000, but the cases are more evenly distributed, with a peak in December and the following September.

Limitations of the model

Before we draw any conclusions, let me emphasize that this is a very simple model. It doesn’t take into account the fact that various parts of the country will experience the virus differently. We may see spikes in some areas and growth in others. State and local policies will, in the end, dictate the outcome of a herd immunity strategy, and they may be vastly different in each area depending on the situation on the ground.

Furthermore, the scenarios above assume a completely linear drawdown of controls, which is impossible. In reality, the new cases and deaths will surge in unpredictable ways, and authorities will have to respond the best they can to “flatten the curve” on a local level whenever a surge appears imminent.

Conclusions

A possible lower infection fatality rate for coronavirus is very, very good news. But even if the virus turns out to be similar to the seasonal flu in that regard, it doesn’t change the need to implement controls to prevent our hospitals from being overwhelmed by patients.

What a lower rate does signal is that we have a potential way out of lockdown with a gradual drawdown of social distancing guidelines over the course of the year, and perhaps next year as well. However, that assumes that recovered individuals gain immunity, which is still up in the air. The WHO said on April 24th that “There is currently no evidence that people who have recovered from Covid-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection."

A herd immunity strategy might work, if we are willing to accept a few hundred thousand deaths. The key is to spread out the cases over time, so a sudden “grand reopening” is simply not possible. But, if we’re smart about it, we can beat this thing and get the economy going again at the same time.

Want to see the model for yourself, make a copy, and test your own assumptions? Access it here: